Is Service Learning the Best Approach to Ethical Study Abroad?

/Service learning is a common component of study abroad, especially faculty led study abroad programs which are rapidly growing in popularity. Service learning is a type of "community-based learning," but it might not always be the right choice for faculty seeking to create meaningful impact on both their students and the host community.

This post is based on a presentation Learn from Travel founder, Roman Yavich, made in collaboration with Laura Ochs and Tanyshia Stevens from Agnes Scott College, at NAFSA Region 7 conference in Jackson Mississippi, in November 2025. We presented a variety of approaches to community based programming in study abroad, highlighting the pros and cons of each and presenting a framework for evaluation of community impact. We highlight the importance of the financial contribution to host community institutions and the local economy.

The slides for the presentation can be downloaded here, along with the case study handout and the evaluation rubric.

The Spectrum of Community Engagement

Not all interactions with host communities during a study abroad program are created equal. Faculty-led programs engage with communities in a variety of ways, spanning a spectrum from structured service to simple shared experiences and conversation:

Service Learning: Historically focused on students providing a direct service as a component of their academic work.

Workshops: Educational, hands-on experiences for visiting students to learn from local experts

Peer-to-Peer Engagement: Collaborative, interactive experiences with local students, ideally with a focus on reciprocity

Community Site Visits: Primarily observational experiences, which ideally facilitate cultural immersion.

Conversations / Meetings / Discussions: Informal dialogue, often facilitated as part of a community visit.

While each of these types of community-based learning can be absolutely transformative for the students, truly ethical community-based programming prioritizes the host community’s needs and goals, at least as much as those of the students. On the contrary, this model of learning can be exploitative and reinforce many of the colonial paradigms study abroad is intended to break.

Students and faculty are usually interested in service learning in order to provide a benefit to the host community, but the time and effort invested into these projects by the local community and host institutions is often undervalued, while the product of the service performed is often overvalued. When we correctly assign value to the inputs and outputs of service learning, the net impact of many projects is negative. On the other hand, because the input required by the host community is much lower for other community-based activities, the net value is usually positive.

A Case Study in Partnership: Peer to Peer Exchange with Students in Belize

An effective community-based approach centers on reciprocity. This ethos is shared by one of our long-time clients, Agnes Scott College. We recently presented on the topic at the NAFSA Region 7 conference, where our colleagues from ASC shared several case studies that exemplify ethical community-based programming.

Studetns from agnes scott college conducting an environmental impact assessment in a natural area with peers from galen university in belize

One such program in Belize involved a Peer-to-Peer exchange with the Belizean Galen University students. Rather than U.S. students performing a service for the community, both sets of students collaborated on a shared assignment: an Environmental Impact Assessment. U.S. students worked with their Galen University peers throughout the semester and presented their findings once they arrived in Belize. In this model, both groups acted as co-educators, ensuring the learning and the output were mutually beneficial and locally relevant. The local faculty did not have to deviate from their standard curriculum or spend a significant amount of time on organizing a service project. Learn from Travel even made a donation to Galen University to compensate for the administrative efforts.

Panama Service Learning Case Study

Learn from Travel has partnered with a rural community in Panama for five years to offer an incredible service learning program to students from Cal Poly. The course is centered on sustainability and sustainable design and construction. Students travel to Panama and for two days build an adobe house (casa quincha) with local residents who design and guide the process. The construction technique which employs locally sourced clay and hay to make an adobe mix, has been used in this area for centuries, but is slowly becoming forgotten as cement and other materials have become available. New materials cost more, are less durable, and have a bigger environmental footprint. The elders of this community are keen to share their knowledge with the youth, and so our project provides them with this opportunity. Learn from Travel pays for all of the materials and the food which traditionally accompanies a community gathering to complete the construction. The house is then donated to a family in the community, the same way it has been done for centuries.

The financial contribution we make to the community, the opportunity to gather in celebration and pass on important skills to future generations, are all positives that outweigh the time and effort invested by the community. A description of this program can be found here. Below is a video summarizing the impact of this program on the students.

Positive and Negative Impacts

Community engagement activities can have profound and often unintended consequences. An honest evaluation must consider both the potential benefits and the ethical risks.

Positive Impacts

When executed thoughtfully, community-based activities can offer:

Financial contribution: Direct and fair compensation to local partners

Potential for long-term relationship and ongoing collaboration

Respectful cultural exchange that moves beyond surface-level interactions

Negative Impacts

Without careful planning, programs can inadvertently cause harm:

Subpar Quality of Service Work: Unskilled student labor often produces work that local organizations must later fix or maintain.

Undermining Local Culture: Unreflective engagement can introduce or promote capitalistic values, creating a negative social impact.

Lack of Funds for Ongoing Maintenance: Building new infrastructure (gardens, buildings, etc.) without a plan for long-term maintenance leaves the host community burdened.

Distraction from Ongoing Work: Requiring local partners to dedicate significant time to supervising students distracts them from their core mission.

Destabilizing Effect on the Host Community: Inconsistent or poorly planned projects can create instability or dependency.

Best Practices for Ethical Engagement

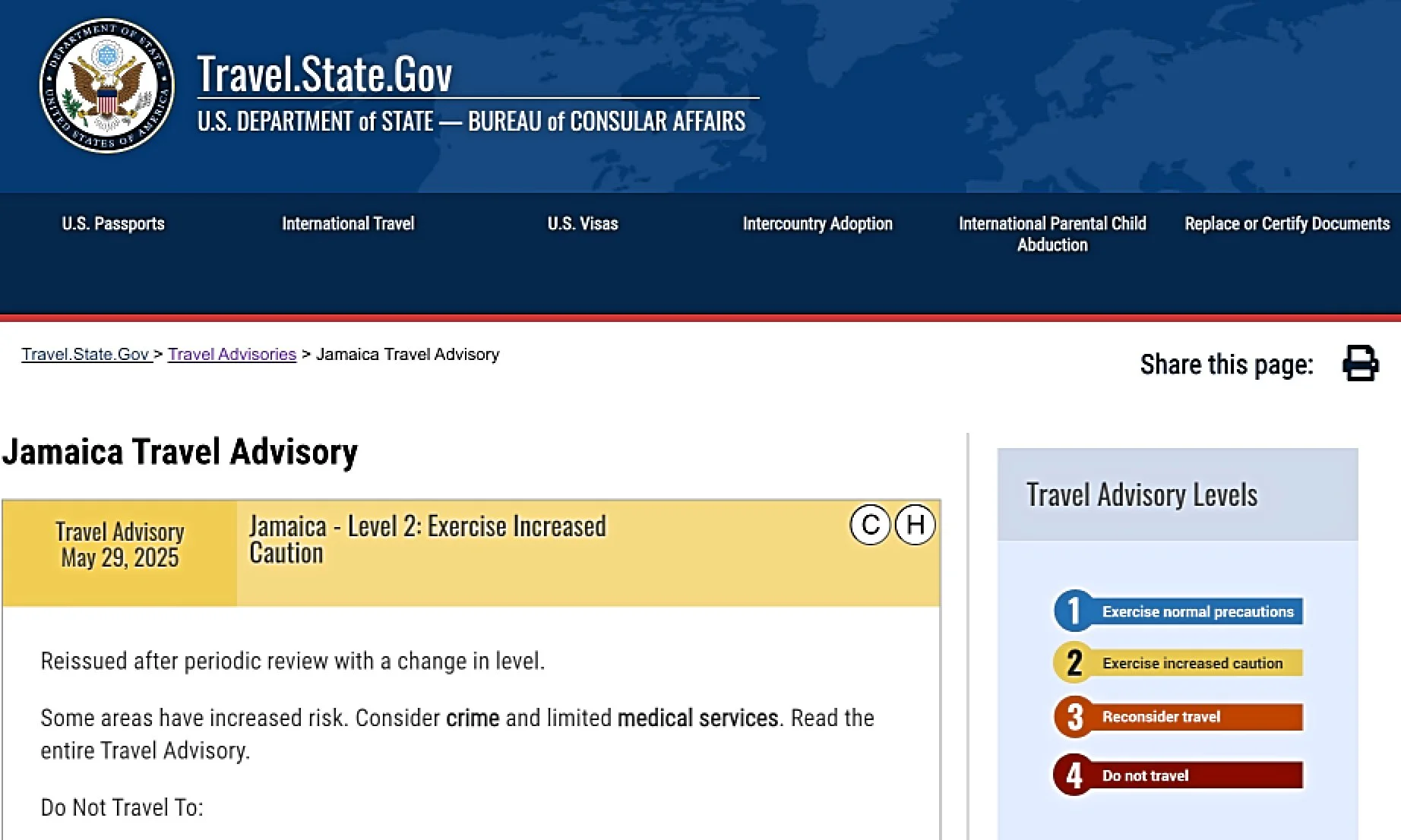

To mitigate negative impacts and ensure ethical practice, we recommend the following best practices:

Prioritize Financial Contribution Over Service: Direct, fair monetary support is often the most respectful and sustainable form of contribution.

Challenge Providers: Work with providers who are willing to rethink and move beyond a purely "touristic" approach to community interaction, prioritizing the actual benefits to the host community. .

Formal Training for Cultural Exchange: Implement structured training (like GlobalUp) to prepare students for meaningful and respectful cross-cultural interactions.

Strategic Planning and Reflection: Plan activities with clear objectives, incorporate guided reflection while abroad, and include follow-up reflection upon return.

Community Partners in Leadership Roles: Ensure community partners are in leadership roles, guiding the work, defining the needs, and maintaining ownership over the projects.

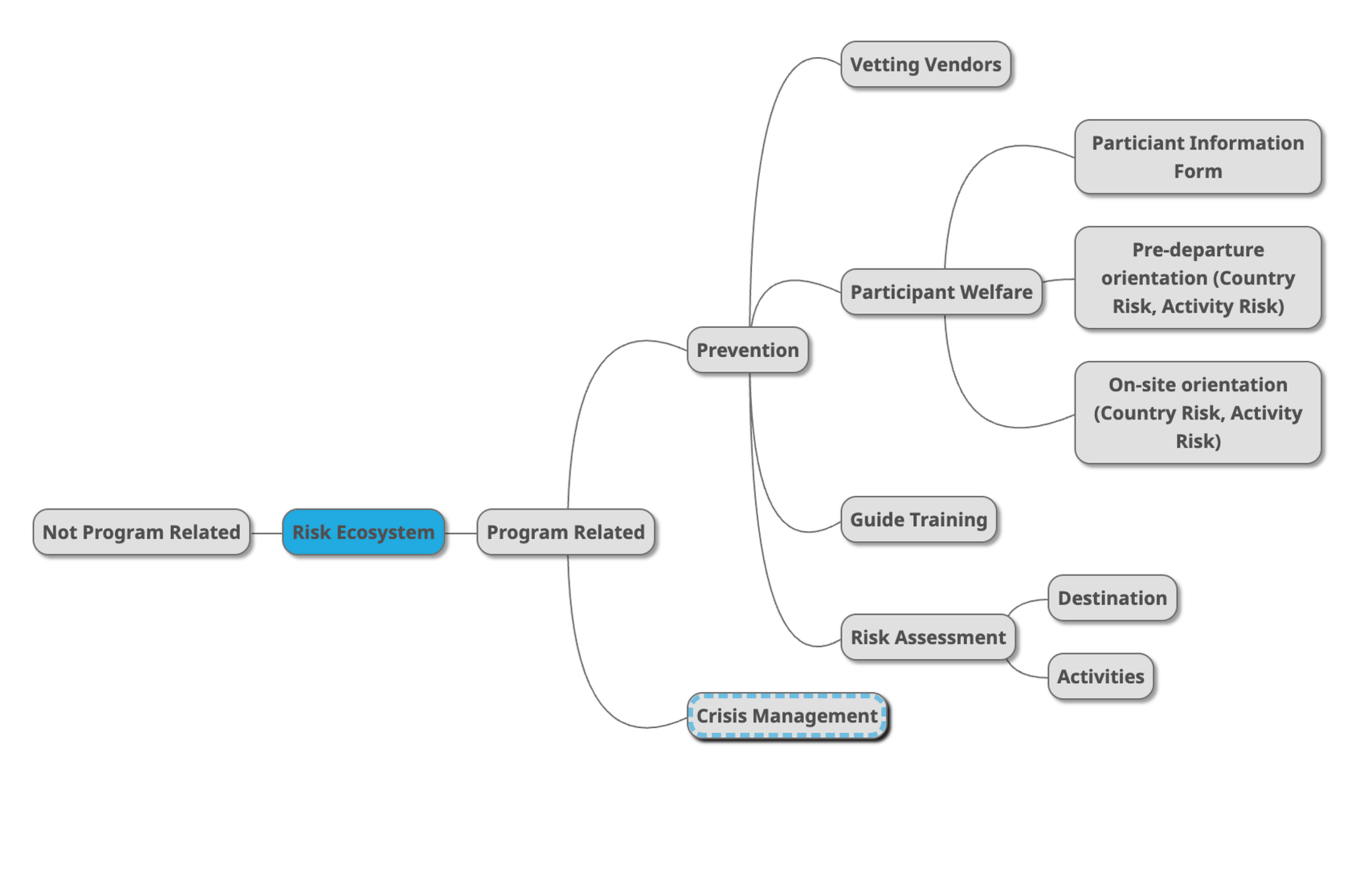

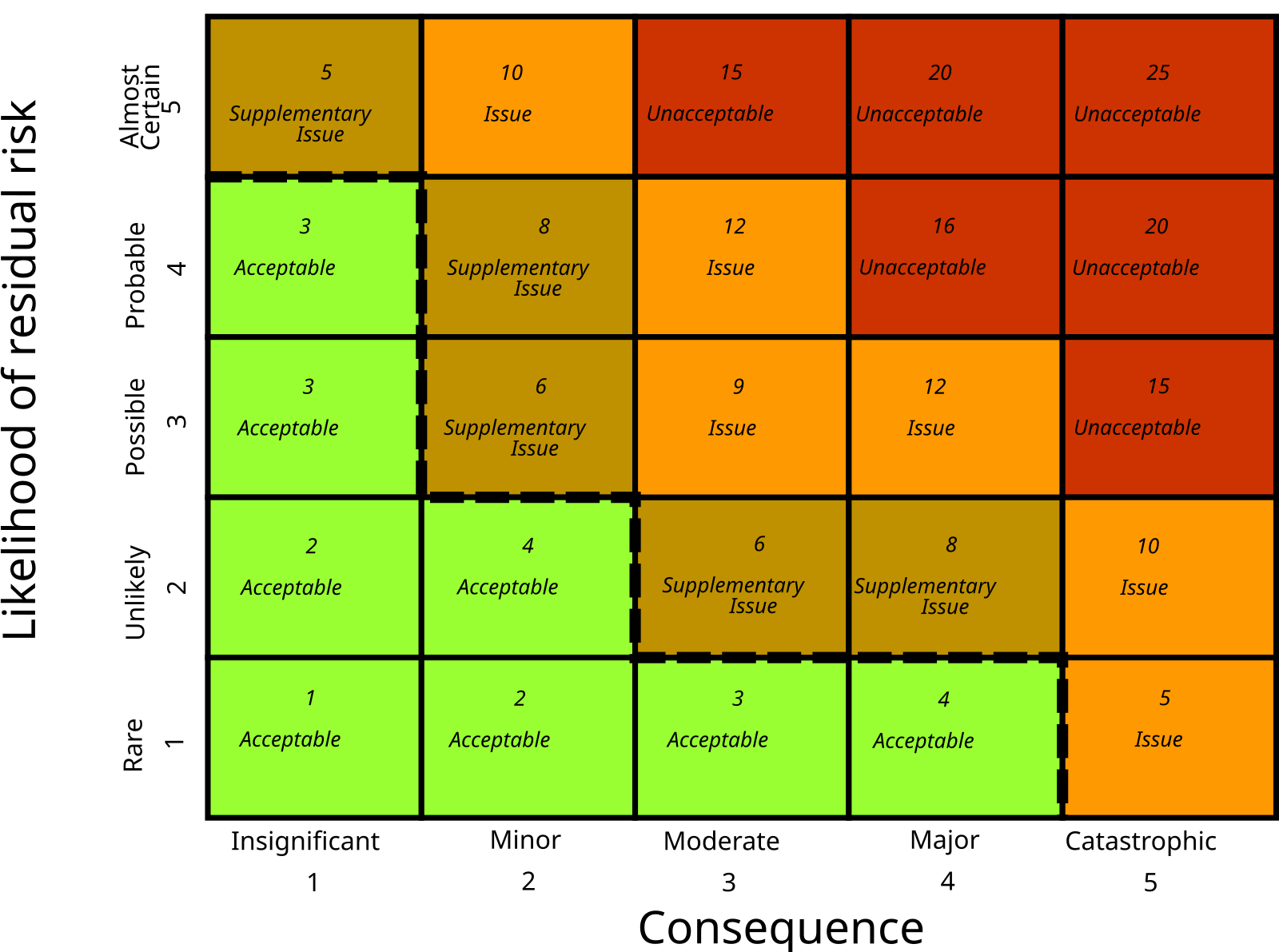

A Simple Framework for Evaluation

The difference between a "lacking" program and an "excellent" one can be quickly assessed and compared using a simple framework. This rubric provides a tool to evaluate whether your program is truly community-based and ethical:

Planners can Compare programs by assessing these categories and summing up the points.

By moving past the label of "service learning" and embracing a truly community-based approach—one where partnership, ethics, and local ownership are prioritized—you ensure your faculty-led programs create lasting, positive value for everyone involved.